If you asked scholars to name the most important happenings in the last 50 years of American history, they would likely list events ranging from the Vietnam war, the Civil Rights Movement, invention of the computer chip, the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, the Great Recession that officially lasted from 2007 to 2009, and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Missing from this list would be the so-called Nixon Shock, the 50th anniversary of which is upon us.

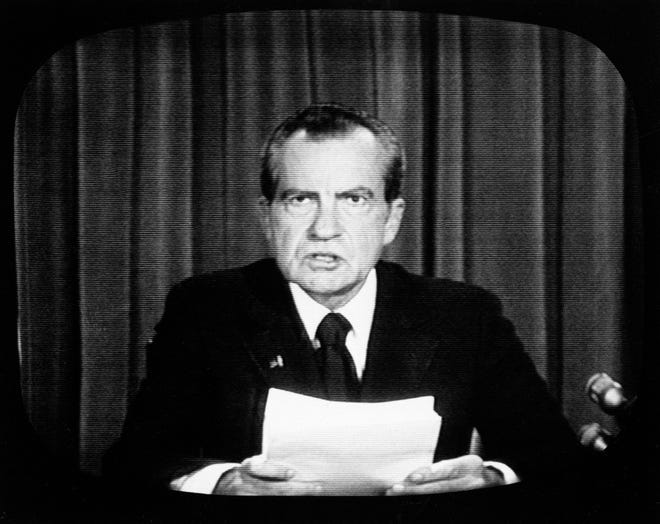

In a televised address on Aug. 15, 1971, President Nixon (America’s very own Richard III) announced that he was “closing the gold window,” ending the dollar’s convertibility into gold. Unilaterally ending the last vestiges of the gold standard and eliminating the final link between gold and the dollar was a consequential moment in U.S. financial history.

The Nixon Shock had profound implications for the U.S. and the global economy. The U.S. unleashed an era of floating exchange rates, which created a much less stable world economy, since currency values fluctuated due to the disconnect between them and something that was tangible. Many contend it was the beginning of an inflationist era of fiat money and created decades of turbulence in currency markets.

The president announced the end of the American commitment to redeem other countries’ dollars for gold at $35 an ounce, a bedrock of the Bretton Woods system of mostly fixed exchange rates that had been in place since 1944 and established the dollar as the world’s reserve currency.

Closing the gold window marked the end of a commodity-based monetary system and the beginning of a new world of fiat currencies backed entirely by the full faith and trust in the government that issued it. This gave the government and the Federal Reserve greater control over the economy because they can control how much money is printed.

The president’s main concern in 1971 was avoiding a recession that might cost him the 1972 election. He strong-armed Federal Reserve Chair Arthur Burns into keeping interest rates low in the face of rising consumer prices. President Nixon allegedly told the Burns, “we can take inflation if necessary, but we can’t take unemployment”, setting the stage for the birth of the Great Inflation of the 1970s, the Age of Aquarius.

In fairness to President Nixon, he inherited an economy from President Johnson that was under serious strain. Federal spending to simultaneously fight the Vietnam War and build the Great Society created budget deficits that fueled inflation along with the growing U.S. trade deficit.

The U.S. had printed more dollars than it could back with gold. Inflation had started to rise in the second half of the 1960s, soaring from a mere 1.4 percent in 1960 to 13.5 percent in 1980.

Put plainly, too many dollars were abroad. By 1971, the pledge that an ounce of gold was worth $35 became void. The feds could not make it happen. So, they severed the link. The value of the dollar in foreign exchange markets suddenly plummeted, which caused increases in import prices as well as in the prices of most commodities priced in dollars.

For sure, the Nixon Shock was not the only reason for the accelerating inflation of the 1970s. For example, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Counties announced an oil embargo against the U.S. during the October 1973 Yom Kippur War in Israel. Oil prices surged by 400 percent and U.S. economic activity instantly dropped. In 1973 the U.S. entered into the deepest recession since the Great Depression, but this time it was coupled with price inflation, not the deflation of the 1930s.

The Nixon Shock was another painful example of the politicization of the economy. Sound familiar? A key lesson for today is that price stability is paramount for a strong and growing economy. Tolerating high inflation in an effort to stimulate the economy is a dangerous game to play.